"Argh! Fuck y'all! I'm not public property!" So growls country star Maury Dann in the little-known 1973 character study Payday. A road movie taking place over two frenzied, pill-popping, Wild Turkey-guzzling, bird-hunting and groupie-fucking days, Rip Torn gives it his Method-acting best as the kind of man who knows he can create any kind of mess and his handlers will pick up the bill. "You're just a rich little child with a lot of toys," a woman tells him, but you've pretty much figured that out by that point. Payday invokes the madness of the road--if it doesn't quite achieve full-on insanity, it reaches a decent point of intoxication and sleepless edginess.

"Argh! Fuck y'all! I'm not public property!" So growls country star Maury Dann in the little-known 1973 character study Payday. A road movie taking place over two frenzied, pill-popping, Wild Turkey-guzzling, bird-hunting and groupie-fucking days, Rip Torn gives it his Method-acting best as the kind of man who knows he can create any kind of mess and his handlers will pick up the bill. "You're just a rich little child with a lot of toys," a woman tells him, but you've pretty much figured that out by that point. Payday invokes the madness of the road--if it doesn't quite achieve full-on insanity, it reaches a decent point of intoxication and sleepless edginess.

Dann is equal parts Hank Williams and Barnum & Bailey, but he's got the attributes reversed: he's not that talented in the art of country music but can certainly take advantage of all the suckers that surround him; he likes to get fucked up but actually might not be that great of an entertainer. Despite ostensibly taking place in the honky-tonks of the era, only the opening sequence gives any real glimpse of that world, with Torn wailing away on the corny "She's Just a Country Girl," (all songs are by Shel Silverstein) winking and mugging to the desperately unhip patrons.

The face Dann presents to his fans is one much different from the one he shows in the backrooms and hotel rooms and parking lots and even at his old mother's rundown rural home. Sly, charming, and ingratiating when socializing with regular folk, he's willful and destructive behind the scenes and not above cheaply "seducing" one of the prettier "unhip" patrons or smarmily trying to get out of a speeding ticket. Still it's painful to watch the his humiliation at having to brown-nose an unctuous DJ ("Pigfucker son of a bitch") at a hick radio station, trying to get out of a public appearance by presenting the guy with a bottle of Wild Turkey while on the air ("Here's some game birds I shot"). We can see how promoters pressured and used veiled threats on stars--and how much the artists resented it but felt powerless to fight back. But Maury Dann is not exactly afraid of fighting back. He's a precursor to the "outlaw country" stars like Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson that would soon rejuvenate the genre.

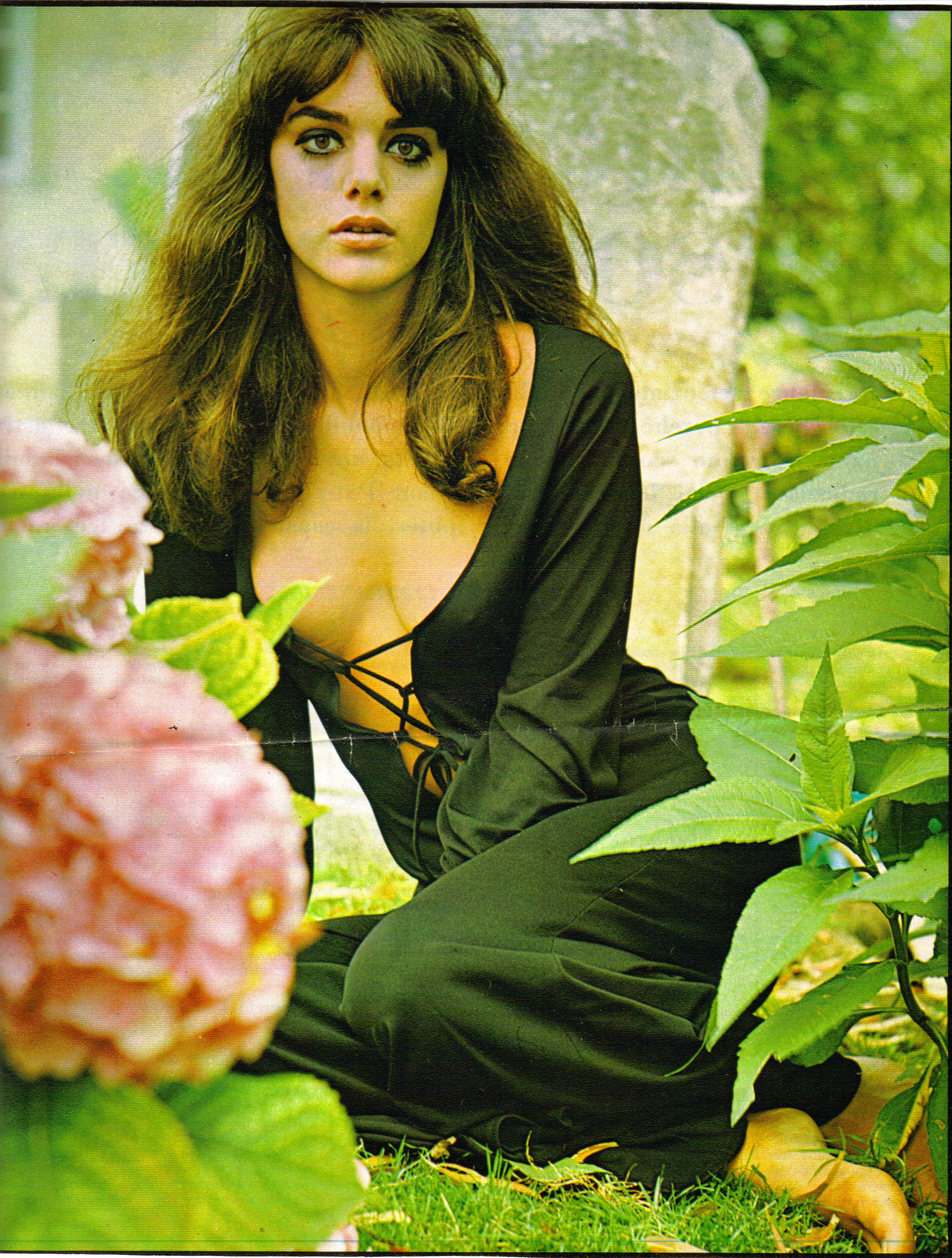

His manager, no-nonsense, Pepsi-swilling Bob (Jeff Morris) routinely gets Dann out of scrapes ("I don't care how you fix it, get me out of this town tonight"), and the affabale, chauffeur/wanna-be chef Chicago (Cliff Emmich) does whatever Dann wants--and eventually takes the biggest fall of all for him. The two women along for the ride are Mayleen (Ahni Capri) his "girlfriend," and Rosamond (Elaine Heilveil ), a young groupie Dann pilfers from his soon-to-be estranged best bud Clarence (Michael Gwynn). Rosamond and Dann have sex in the backseat of his Cadillac while they think Mayleen is asleep next to them. This of course turns out terribly. Mayleen confronts the younger woman in a gas station ladies' room: "You'll never see 21 birddogging other women's men. Get the message?" Rosamond, suddenly wise beyond her years, lights a smoke and coolly replies, "I believe I do--do you?" Zing!

His manager, no-nonsense, Pepsi-swilling Bob (Jeff Morris) routinely gets Dann out of scrapes ("I don't care how you fix it, get me out of this town tonight"), and the affabale, chauffeur/wanna-be chef Chicago (Cliff Emmich) does whatever Dann wants--and eventually takes the biggest fall of all for him. The two women along for the ride are Mayleen (Ahni Capri) his "girlfriend," and Rosamond (Elaine Heilveil ), a young groupie Dann pilfers from his soon-to-be estranged best bud Clarence (Michael Gwynn). Rosamond and Dann have sex in the backseat of his Cadillac while they think Mayleen is asleep next to them. This of course turns out terribly. Mayleen confronts the younger woman in a gas station ladies' room: "You'll never see 21 birddogging other women's men. Get the message?" Rosamond, suddenly wise beyond her years, lights a smoke and coolly replies, "I believe I do--do you?" Zing! But ultimately, all women are expendable, interchangeable, left on the side of the road. Literally so, for Mayleen, abandoned with a wad of cash that Dann tells her is more than she's worth. Uh, zing?

But ultimately, all women are expendable, interchangeable, left on the side of the road. Literally so, for Mayleen, abandoned with a wad of cash that Dann tells her is more than she's worth. Uh, zing?I took great pleasure in seeing the details of period and place as the entourage of good ol' boys swung through the '70s South: men's hair severely parted and oiled, gas-guzzling American cars made of steel and leather, cowboy-style Levi's, enormous belt buckles, and long-sleeved pearl-button-snapped Western shirts that any y'alt.country dude would kill for.

Its screenplay by cult novelist Dan Carpenter, Payday, despite good characterization, seems a tad under-ambitious, indifferently directed by Daryl Duke (Silent Partner). In the dramatic confrontations Torn is doing most of the heavy lifting. Still, the climactic sequence, which finds Dann taking off in a Cadillac into the country in a desperate attempt to escape his fate while ruminating acidly on his childhood, is well-done and keeping quite in character. The title Payday implies not only his getting cash for his appearances but also the movie's final scene. It's worth sticking around for. Grab a bottle of Wild Turkey and enjoy.

Its screenplay by cult novelist Dan Carpenter, Payday, despite good characterization, seems a tad under-ambitious, indifferently directed by Daryl Duke (Silent Partner). In the dramatic confrontations Torn is doing most of the heavy lifting. Still, the climactic sequence, which finds Dann taking off in a Cadillac into the country in a desperate attempt to escape his fate while ruminating acidly on his childhood, is well-done and keeping quite in character. The title Payday implies not only his getting cash for his appearances but also the movie's final scene. It's worth sticking around for. Grab a bottle of Wild Turkey and enjoy.

.jpg)