"When an American cracks up, he opens a window and shoots up a bunch of strangers. When a Japanese cracks up, he closes the window and kills himself."Richard Jordan in The YakuzaThe Yakuza

"When an American cracks up, he opens a window and shoots up a bunch of strangers. When a Japanese cracks up, he closes the window and kills himself."Richard Jordan in The YakuzaThe Yakuza (1974) has a pretty high pedigree for the 1970s: it was the first screenplay from

Paul Schrader, co-written with his brother

Leonard, a rewrite by

Robert Towne, and directed by

Sydney Pollack.

Robert Mitchum, who was having a nice career resurgence at the time, had the lead role. Between them, this is a pretty impressive bunch of credits, encompassing

Chinatown,

The Way We Were,

The Friends of Eddie Coyle,

The Last Detail, and

They Shoot Horses, Don't They?, among others.

At the time, the Schraders were paid an inordinately high fee ($325,000) for the screenplay, which heralded their arrival in Hollywood. Paul would go on to write two of the most acclaimed movies of the era,

Taxi Driver and

Raging Bull, and make his startling directorial debut with

Blue Collar (1978). Pollack, apparently uncomfortable with making solely a "gangster picture," hired Towne to add backstory and romantic elements to the script, and the Schraders distanced themselves. I hope Paul feels differently today (his brother Leonard died several years ago; watch this amazing video of his book-stuffed home

here) because

The Yakuza is a satisfying thriller that showcases many of Schrader's thematic concerns, and Mitchum at his middle-aged best.

Harry Kilmer, played by a wonderfully disheveled, schlumpy Robert Mitchum, is tapped by his old WWII buddy George Tanner (Brian Keith), a business magnate, for a big favor: rescue his college-age daughter from Japanese gangsters, known as the

yakuza. For Kilmer, this is a bittersweet request, as he had remained in Japan after the war to be with his mistress Eiko (Kishi Keiko) and her infant daughter, victims of the bombing raid on Tokyo. After Eiko's brother Tanaka Ken returned from a POW in the Philippines, Kilmer returned to America, but without Eiko - who said she could never marry him.

Kilmer arrives in Japan with young Dusty (Richard Jordan), a confidant of Tanner's, to make sure Mitchum "doesn't get run over by a Honda." They meet up with Ollie Wheat (Herb Edelman), another old war pal who still lives in Tokyo, whose doctor has told him he can't play his beloved chess because of the stress it causes him. "Don't let it fool you," Wheat warns when Kilmer notices an American-style high rise, "Japan is Japan, and the Japanese are still Japanese." As veterans of World War II, even ones who stayed in the country, these men are wary of this place. Immediately following this exchange comes a cry from the other room; Dusty has sliced himself on a specimen from Wheat's sword collection. "I barely touched it," he says. Foreshadowing, anyone? Then Kilmer, "the strange stranger," as he was referred to as an American in Japan after the war, wanders the city streets alone, seeking Eiko after many years.

Soon, Eiko's brother Tanaka Ken (Takakura Ken), once a mighty yakuza but now a master teacher in traditional Japanese swordsmanship, shows up. "Ken is a relic, a leftover of another age, of another country," Kilmer is told, and Ken therefore feels a begrudging obligation to help Kilmer since Kilmer had cared for Eiko after the war. Tanner's daughter is rescued in a terrific shootout in the middle of a yakuza hideout. Although he says he hasn't picked up a sword in 10 years, he saves Dusty and Kilmer with his skill by killing several yakuza. But now the yakuza boss wants Tanaka dead, while Tanner, who reveals his true motivations, makes a deal with them to take out Kilmer...

One can feel the writerly passages that probably entwine both Schrader's and Towne's version of the screenplay in the voice-over narrations that work terrifically, in the discussion of "

giri" and its various meanings, in the elaborations on the value of family, duty, and honor. As for the direction, in some scenes I felt as though I could see the screenwriters (particularly Schrader) over Pollack's shoulder, coaching him through scenes, particularly the sword-and-gun fight sequences, which are well-staged, awesomely violent and very nearly poetic. When Kilmer bundles up in a large coat to hide his weaponry and the camera follows him down a long hallway as he looks for Tanner, we can see a dry-run for the climax of

Taxi Driver. The pre-credit sequence in Japan reminded me of the cabbie boss's interview of Travis Bickle as well, right down to the edits. Schrader's screenplays are just that visual.

Dave Grusin

Dave Grusin's score is highly effective, mysterious, and evocative throughout, during the opening credits, and especially during Kilmer and Eiko's reunion, which are some of my favorite moments in the film. With old friend Wheat narrating, Grusin's music, and subtle editing, we get a real sense of the Kilmer and Eiko's happy past. But there is also loss here, loss that is predicated upon Kilmer's return.

The themes that will preoccupy much of Schrader's best work are all here: the loner on a mission, the man who carefully chooses - like a script - his path of action, men obsessed with guns and violence and redemption, the "spirituality" found in physical confrontation and duty. Violence is theater, something carefully prepared for and performed. "I just thought you might want to hear your reviews," says Wheat to Mitchum after he sees the newspaper account of their rescue of Tanner's daughter. This philosophy of Schrader's would see its apotheosis in his elegant, ambitious

Mishima (1985).

Ultimately this is not a film

about vengeance or violence, but one that uses those elements to explore the past and other people and our duty to them; the characters are honor-bound to one another, across decades, across continents. The movie ends with a true understanding of respect and friendship; after we have seen the turnabouts and double-crossings previously, it is a satisfying, hard-won, and even touching moment. I recommend

The Yakuza easily to people who are fans of any of the aforementioned artists. Like many '70s movies it is at once a genre flick and a character study. This is no anonymous karate or gangster flick; this is a serious, patient meditation on adult concerns punctuated by bursts of bitter, necessary, regretful violence... and the amends men make for it.

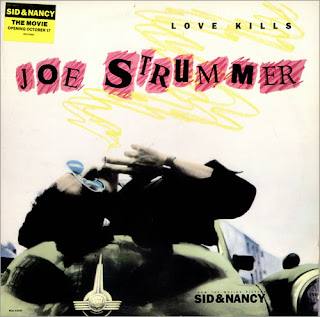

On this day in 2002, the world lost one of rock'n'roll's greatest frontmen, Joe Strummer. Born John Graham Mellor in 1952, he embodied the busking British folkie, squatting in abandoned high rises during the early '70s, and then joined the pub rock ensemble the 101ers. But as a member of the Clash from 1976 to 1986, Joe rounded the world, galvanizing audiences with lyrics exposing global injustice, urban poverty, ghetto criminals, institutional racism, and ruthless political machinations in fiery live performances that still boggle the mind and inspire the heart.

On this day in 2002, the world lost one of rock'n'roll's greatest frontmen, Joe Strummer. Born John Graham Mellor in 1952, he embodied the busking British folkie, squatting in abandoned high rises during the early '70s, and then joined the pub rock ensemble the 101ers. But as a member of the Clash from 1976 to 1986, Joe rounded the world, galvanizing audiences with lyrics exposing global injustice, urban poverty, ghetto criminals, institutional racism, and ruthless political machinations in fiery live performances that still boggle the mind and inspire the heart. Effortlessly mixing the intensity of punk rock with the sounds of reggae, R&B, rockabilly, rap and even some gospel and bizarre sound collages, the Clash were the premier band of their era, particularly with their essential 1979/80 album, London Calling. Today many of the Clash's songs, like "Spanish Bombs," "Tommy Gun," "White Man in Hammersmith Palais," and "Straight to Hell," have become classics and the band has become a part of rock's mythic pantheon of legendary performers, inducted into the Rock'n'Roll Hall of Fame just after Joe's death.

Effortlessly mixing the intensity of punk rock with the sounds of reggae, R&B, rockabilly, rap and even some gospel and bizarre sound collages, the Clash were the premier band of their era, particularly with their essential 1979/80 album, London Calling. Today many of the Clash's songs, like "Spanish Bombs," "Tommy Gun," "White Man in Hammersmith Palais," and "Straight to Hell," have become classics and the band has become a part of rock's mythic pantheon of legendary performers, inducted into the Rock'n'Roll Hall of Fame just after Joe's death. After the Clash broke up, Joe floundered about for over a decade, performing solo at times (I saw him in 1989, a wonderful show). But he returned in 1999 with a new band, the Mescaleros, and a newfound passion for performing. They released two terrific albums, Rock Art and the X-Ray Style and Global a Go-Go. Audiences came in droves, kids too young to have seen Joe during his '70s heyday, and people a generation older who couldn't believe their old hero still had the drive, the chops, the energy of a rock'n'roller half his age. Joe was back to stay, it seemed, reinvigorated and armed with music that spanned the planet and lyrics at once tender and surreal, funny and heartbreaking.

After the Clash broke up, Joe floundered about for over a decade, performing solo at times (I saw him in 1989, a wonderful show). But he returned in 1999 with a new band, the Mescaleros, and a newfound passion for performing. They released two terrific albums, Rock Art and the X-Ray Style and Global a Go-Go. Audiences came in droves, kids too young to have seen Joe during his '70s heyday, and people a generation older who couldn't believe their old hero still had the drive, the chops, the energy of a rock'n'roller half his age. Joe was back to stay, it seemed, reinvigorated and armed with music that spanned the planet and lyrics at once tender and surreal, funny and heartbreaking. But it was not to be. On December 22, 2002, Joe came in from walking his dogs at his country home at Broomfield in Somerset, England, sat in his living room, and died peacefully of a heart condition no one even knew he had - not even himself. He could have died at any time during his 50 years of life. Fortunately, we got many good years of Joe Strummer's intelligence and compassion, his commitment and his insight, his fury and, indeed, his personal style, and for that, I'm ever thankful.

But it was not to be. On December 22, 2002, Joe came in from walking his dogs at his country home at Broomfield in Somerset, England, sat in his living room, and died peacefully of a heart condition no one even knew he had - not even himself. He could have died at any time during his 50 years of life. Fortunately, we got many good years of Joe Strummer's intelligence and compassion, his commitment and his insight, his fury and, indeed, his personal style, and for that, I'm ever thankful.

Joe and the Mescaleros on David Letterman, 2001:

Joe and the Mescaleros on David Letterman, 2001:

.jpg)