Some thoughtful movie fans see American personhood summed up in characters like Rocky Balboa, Atticus Finch, George Bailey, Forrest Gump, Cool Hand Luke, and even Vito Corleone or Tony Montana. But I see much of it in Travis Bickle, the wounded Vietnam vet and desperate loner of Taxi Driver (1976), slowly going psychotically mad in the (then-) ruined urban landscape of New York City. It is my contention that this film, with its noxious stew of stalker/vigilante fantasy, misguided heroism, a war-wounded mind, racism, sexism, urban decay, gun fetishism, and misplaced media attention, is the greatest American film since its release in 1976. Really. I cannot put it any other way. It's an all-too-prescient depiction of a personality disorder that would come to haunt our public life in the following decades: men broken who refuse to mend. Their name is legion and I need not mention them here. Gaze into the abyss, a man adrift and alone:

Some thoughtful movie fans see American personhood summed up in characters like Rocky Balboa, Atticus Finch, George Bailey, Forrest Gump, Cool Hand Luke, and even Vito Corleone or Tony Montana. But I see much of it in Travis Bickle, the wounded Vietnam vet and desperate loner of Taxi Driver (1976), slowly going psychotically mad in the (then-) ruined urban landscape of New York City. It is my contention that this film, with its noxious stew of stalker/vigilante fantasy, misguided heroism, a war-wounded mind, racism, sexism, urban decay, gun fetishism, and misplaced media attention, is the greatest American film since its release in 1976. Really. I cannot put it any other way. It's an all-too-prescient depiction of a personality disorder that would come to haunt our public life in the following decades: men broken who refuse to mend. Their name is legion and I need not mention them here. Gaze into the abyss, a man adrift and alone: It's well-known film lore now that Paul Schrader wrote this screenplay in a matter of weeks after a bout of homelessness, drinking while walking the streets and sleeping in his car. "It leapt out of me like an animal," he would say later. His choice of a taxi cab to symbolize loneliness while in the midst of humanity was truly inspired. The primal power of the script is undeniable, even though it was restructured in the final edit.

It's well-known film lore now that Paul Schrader wrote this screenplay in a matter of weeks after a bout of homelessness, drinking while walking the streets and sleeping in his car. "It leapt out of me like an animal," he would say later. His choice of a taxi cab to symbolize loneliness while in the midst of humanity was truly inspired. The primal power of the script is undeniable, even though it was restructured in the final edit. Director Martin Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Chapman use an astonishing expressionistic style to bring Schrader's words alive. For all its American-ness, this is a movie filled with foreign influences: informed fans will sense a melange of Godard, Bresson, and Dreyer in its execution; those not so inclined will still see something of power and conviction, pain and obsession. Virtually every shot includes Travis Bickle (Robert DeNiro), usually alone in the frame, as everything around him contributes to his despair. He is as responsible for his condition as he is trapped by it.

Director Martin Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Chapman use an astonishing expressionistic style to bring Schrader's words alive. For all its American-ness, this is a movie filled with foreign influences: informed fans will sense a melange of Godard, Bresson, and Dreyer in its execution; those not so inclined will still see something of power and conviction, pain and obsession. Virtually every shot includes Travis Bickle (Robert DeNiro), usually alone in the frame, as everything around him contributes to his despair. He is as responsible for his condition as he is trapped by it. Travis scribbles in his journal with a grade-school pencil (cf. Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest) but it's not only Travis's voice-over narration that clue us in; it's snatches of dialogue, of song lyrics, the inventive camerawork, and Bernard Herrmann's glorious and final jazz-horror score which reveal the man's sickest, most feverish thoughts. "I got some bad ideas in my head," he tells fellow cabbie Wizard (Peter Boyle), and Scorsese relentlessly illustrates them on-screen. I find this strange formality one of Taxi Driver's most fascinating aspects, which I'll focus on here rather than rehashing the plot or performances.

Travis scribbles in his journal with a grade-school pencil (cf. Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest) but it's not only Travis's voice-over narration that clue us in; it's snatches of dialogue, of song lyrics, the inventive camerawork, and Bernard Herrmann's glorious and final jazz-horror score which reveal the man's sickest, most feverish thoughts. "I got some bad ideas in my head," he tells fellow cabbie Wizard (Peter Boyle), and Scorsese relentlessly illustrates them on-screen. I find this strange formality one of Taxi Driver's most fascinating aspects, which I'll focus on here rather than rehashing the plot or performances.

Travis's famous "morbid self-attention" does not result in a sense of self-awareness; it shows a serious lack of one. Those journal entries serve as an ironic counterpoint to his daily life alone in his filthy room (in the screenplay, when Travis leaves his place for the final time, we see it is in a condemned building). Two moments are standouts:

"You're only... as healthy... as... you... feel."

"You're only... as healthy... as... you... feel."

In other instances, dialogue by other characters function as Travis's interior monologue. While the camera focuses on Travis, characters continue talking but we are not really hearing them; it's as if we're inside Travis's head, hearing his very thoughts. First is Wizard relating another of his tall tales about taxi life, two gay men in a fight in his cab; the words are painfully accurate after his date with Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) fails spectacularly:

"They start arguing, they start yelling... you bitch, you whore..."

"They start arguing, they start yelling... you bitch, you whore..."

Fellow cabbie Charlie T's innocent comment about Travis's wad of cash (and all that money never buys Travis a ticket out of this cesspool) proves an ominous warning. He also jokingly calls Travis "Killer." Soon all will be literalized:

The seething black man screaming as he storms down the street while Travis stalks underage hooker Iris (Jodie Foster) delves further into Travis's crumbling mind in the most simplistic terms:

"When I get my hands on that bitch I'm gonna kill her..."

"When I get my hands on that bitch I'm gonna kill her..."

And of course the porn soundtrack Travis can't seem to live without, as a voracious actress expresses her admiration for a large "weapon":

"Look at the size of that... oh yeah... it looks so good..."Even non-essential flirty banter has its place; witness Tom (Albert Brooks) and Betsy at work in Senator Palantine's headquarters. These scenes are not in Schrader's original screenplay, but they are still integral to the film. Are we to take their words at face value, or are they a horrifying prophetic foreshadowing?

Horrifying prophetic foreshadowing.

Horrifying prophetic foreshadowing.In perhaps the film's most revealing and discomforting sequence (prior to the climax of course), director Scorsese himself, looking like an upstanding Manson, glowers maniacally in the backseat of Travis's cab. The living, breathing embodiment of the ugliest thoughts in Bickle's head, he rattles off his intent: to kill his wife--with a .44 Magnum, of course--who's sleeping with a black man. Except he relays this in some of the most repulsively sexist and racist comments that have ever been uttered in a mainstream picture. Travis says nothing, but the glare in his eyes says everything. The passenger exists both as a manifestation of Travis's darkest fears and as an element in the outside world that Travis focuses on solely.

The previous scene showed us Travis condemning Betsy to hell for rejecting him; in the very next sequence, as Travis walks out of the Belmore Cafeteria, an all-night cabbie haunt, he stops and glares at a young black man, who glowers back. When Travis meets up with gun salesman Easy Andy, the first thing he asks is, "You got a .44 Magnum?" All the pieces are falling into place.

"Goddamn, man... Goddamn..."

"Goddamn, man... Goddamn..."

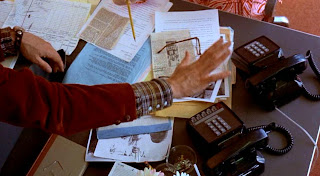

Everyone focuses on the "You talkin' to me?" scene, beloved of dude-movie fans everywhere, but the really effective scenes are simply Travis alone in his room, alone with his fears, his fantasies, and his guns. Scorsese, always ready with an appropriate rock song to illustrate his characters' internal conflicts and desires, nails Travis's with Jackson Browne's "Late for the Sky." Ostensibly a plaintive, earnest tune about a broken relationship, here it becomes an elegy for a forgotten man.

Lastly: throughout the film Scorsese intersperses dramatic overhead and high-angle shots, almost haphazardly. It's first seen in the opening when Travis is being interviewed for the cab driver job. We see it next when he futilely hits on the ticket-taker girl at the porno theater. Then, when Travis boldly confronts Betsy and asks for a date ("I see all this and it means nothing"). And lastly, ultimately, most startling of all, the long tracking shot from the ceiling in Iris's bedroom, now the scene of slaughter. These shots have predicted the film's climax and reach their apotheosis in a gory tabloid of pulp genius.

Whew. This was a tough post to write. Surely I am not the only one for whom revisiting this classic is an emotionally exhausting experience, painful but rewarding. Travis Bickle is a sort of Hamlet character, in which a myriad of interpretations of his behavior and actions seem to say much but in the end do no justice. "He seems to have wandered in from a land where it is always cold," Schrader describes him in the screenplay's opening passages, "a country where the inhabitants seldom speak." Better to watch safely, then, at a distance, comfortable in the theater or at home. But then that is something men like this would never allow us to do.

Whew. This was a tough post to write. Surely I am not the only one for whom revisiting this classic is an emotionally exhausting experience, painful but rewarding. Travis Bickle is a sort of Hamlet character, in which a myriad of interpretations of his behavior and actions seem to say much but in the end do no justice. "He seems to have wandered in from a land where it is always cold," Schrader describes him in the screenplay's opening passages, "a country where the inhabitants seldom speak." Better to watch safely, then, at a distance, comfortable in the theater or at home. But then that is something men like this would never allow us to do.

"On every street corner there's a nobody who dreams of being somebody..."

"On every street corner there's a nobody who dreams of being somebody..." Schrader, Scorsese, & DeNiro share big laughs on location

Schrader, Scorsese, & DeNiro share big laughs on location

.jpg)